ART AS VESSEL OF HISTORY: Emotional Reflections on Culture, Nation and the Manunggul Jar

This essay, which was a requirement for an Anthropology subject during my MA days [1] first appeared publicly in http://artesdelasfilipinas.com/main/archives.php?pid=50. Since then, this essay is now second top search in Google for “Manunggul Jar,” one of the most important Philippine artifact and probably the earliest Filipino artwork. It has been cited in theses. something I can claim my own classic piece. Complicated now by more anthropological theories, I would still not change a thought from this “juvenile” essay. It may well have defined my constant core message yesterday, today and in the years to come, my testament to my people:

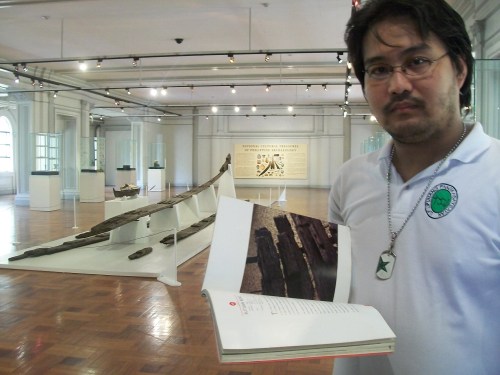

Xiao Chua marvels at the Manunggul Jar, National Art Gallery temporary exhibit, 23 September 2010. Photo by a panda, Xiao Chua Archives

“…the work of an artist and master potter.”

-Robert Fox

27th April 1995—I was walking towards a very familiar building with my Auntie Edna. I was eleven years old then yet I remember the majesty of climbing those steps and walking past the Neo-classical Roman columns until I was inside the Old Congress Building. That was my first visit to the National Museum, the repository of our cultural, natural and historical heritage.

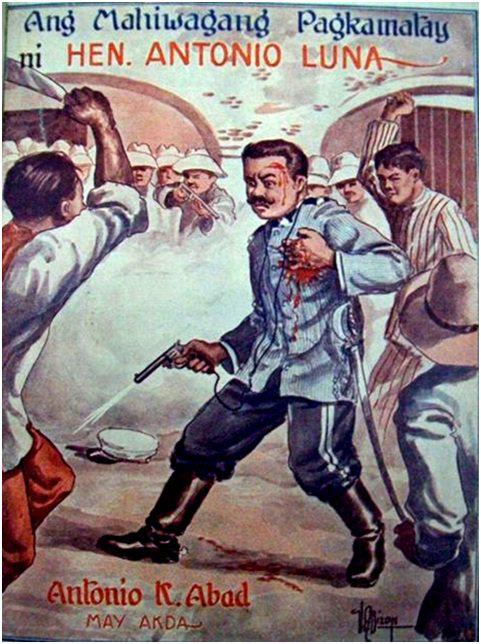

Today, if the Metropolitan Museum’s identifying piece is the painting Virgenes Cristianas Expuestas Al Populacho by Hidalgo and the GSIS Museum its Parisian Life by the painter Juan Luna, the National Museum’s is of course El Spoliarium, Luna’s most famous piece. Many people come to the museum just for this painting. But another less-popular but very significant piece would be that jar—the Manunggul Jar.

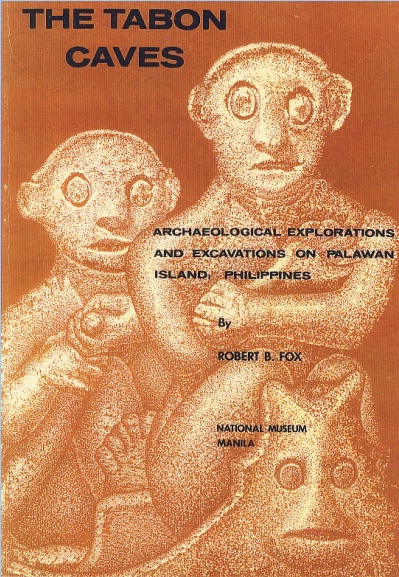

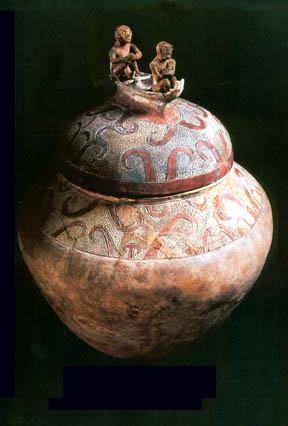

The Manunggul Jar was one of the numerous jars found in a cave believed to be a burial site (Manunggul, part of the archaeologically significant Tabon Cave Complex in Lipuun Point, Quezon, Palawan) in March 1964 by Victor Decalan, Hans Kasten and several volunteer workers from the United States Peace Corps.[2] The Manunggul burial jar is unique in all respects. Dating back to the late Neolithic Period at around 710 B.C.,[3] Robert Fox described the jar in his landmark work on the TabonCaves:

“The burial jar with a cover featuring a ship-of-the-dead is perhaps unrivalled in Southeast Asia; the work of an artist and master potter. This vessel provides a clear example of a cultural link between the archaeological past and the ethnographic present. The boatman is steering rather than padding the “ship.” The mast of the boat was not recovered. Both figures appear to be wearing a band tied over the crown of the head and under the jaw; a pattern still encountered in burial practices among the indigenous peoples in Southern Philippines. The manner in which the hands of the front figure are folded across the chest is also a widespread practice in the Islands when arranging the corpse.

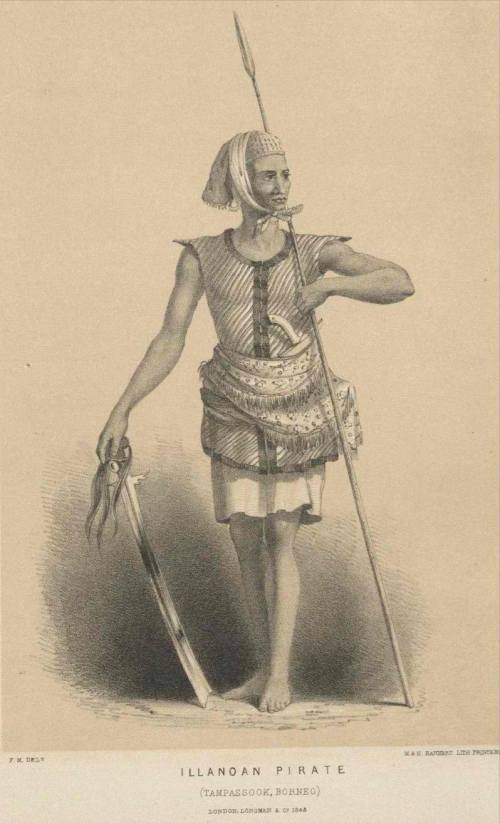

“The carved prow and eye motif of the spirit boat is still found on the traditional watercraft of the Sulu Archipelago, Borneo and Malaysia. Similarities in the execution of the ears, eyes, nose, and mouth of the figures may be seen today in the woodcarving of Taiwan, the Philippines, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.[4]”

My familiarity with the Manunggul Jar in 1995 was because of the picture of it printed on the then new one thousand-peso bill. Seeing the real thing for the first time and knowing it was a burial jar aroused in me a fascination tempered with the creeps. I saw the artistry of the early Filipinos reflected in those fine lines and intricate designs. We were not as dumb as the Spaniards told us we were. My eleven year old self was allowed to take a snap shot of the jar.

After a few years, when I took a Cultural History subject during my BA in History in UP Diliman under Dr. Bernadette Lorenzo-Abrera, the Manunggul Jar was given a whole new meaning for me. When an archaeological find is explained anthropologically, it is imbibed with far-reaching implications in the re-writing of history.

The Manunggul Jar tells us of our connections with our Southeast Asian neighbors. The design is a proof of our common heritage from our Austronesian-speaking ancestors despite the diversity of the cultures of the Philippine peoples.[5] Traces of their culture and beliefs can still be seen in different parts of the country and from different Philippine ethno-linguistic groups, reminding us that there can be a basis for the so-called “imagined community” called the Filipino nation.

The Manunggul Jar tells us of how important the waters were to our ancestors. Before the internet, the telephone, the telegram, and the plane, the seas and the rivers were their conduit of trade, information and communication.[6] In the Philippine archipelago, that, according to Peter Bellwood, the Southeast Asians first developed a sophisticated maritime culture which made possible the spread of the Austronesian-speaking peoples to the Pacific Islands as far Madagascar in Africa and Easter Island near South America.[7] Our ships—the balanghay, the paraw, the caracoa, and the like—were considered marvelous technological advances by our neighbors that they respected us and made us partners in trade, these neighbors including the imperial Chinese.[8]

Xiao Chua with the balanghay Butuan 1, evidence of early boat making and sophisticated maritime culture by ancient Filipinos as early as third century AD found in Butuan City.

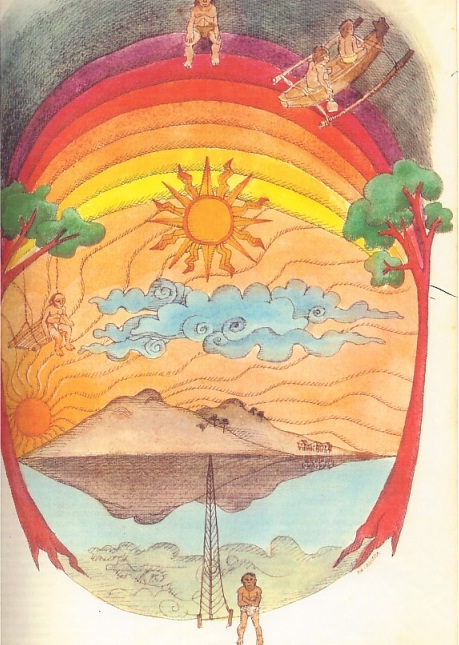

The Manunggul Jar shows that our maritime culture is so paramount to us that it reflected our ancestor’s religious beliefs. Many epics around the Philippines would tell us of how souls go to the next life aboard boats, passing through the rivers and seas. The belief is very much connected with the Austronesia belief in the anito. Our ancestors believed that man is composed of the body, the life force called the ginhawa, and the kaluluwa. The kaluluwa, after death, can return to earth to exist in nature to guide their descendants.[9] This explains why the design of the cover of the Manunggul Jar features three faces, those of the soul, of the boat driver, and of the boat itself. For them, even things from nature have souls, have lives of their own. That’s why our ancestors respected nature more than those who thought that it can be used for the ends of man.

Seeing the Manunggul Jar, I’m reminded not only of the craftsmanship of the early Filipinos, but also of our ancestor’s greatness and of their concept of kaluluwa—those who have it have mabuting kalooban and are merciful. The kaluluwa gives life, mind and will to a person.[10] If this was what our ancestors valued, then our nation is not only great, we are also compassionate.

Illustration of the worldview and belief in the afterlife of early Filipinos in Palawan. Photo from the Dante Ambrosio-Xiao Chua Archives.

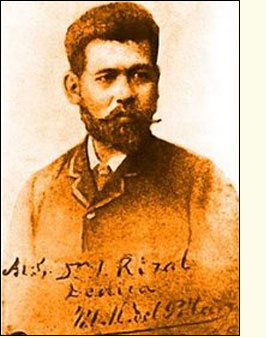

Although our colonial masters in the past told us we are no good and tried to erase our ancestors’ legacies and values, and despite the media today showing how shameful, miserable and poor our country is, from time to time there would be people who echo the same values that our ancestors lived by. In the 1890s, the Katipunan movement of Andres Bonifacio which spearheaded the Philippine Revolution also tried to revive the values of magandang kalooban.[11] During the People Power Uprising of 1986, we showed the world the values of Pananampalataya, Pakikipagkapwa, Pakikiramay, Pagiging Masiyahin, Bayanihan, Pagiging Mapayapa, and Pagiging Malikhain which are deeply rooted in our culture.[12] It was our national hero José Rizal who once said, in his essay Filipinas Dentro de Cien Años (The Philippines Within a Century):

“With the new men that will spring from her bosom and the remembrance of the past, she will perhaps enter openly the wide road of progress and all will work jointly to strengthen the mother country at home as well as abroad with the same enthusiasm with which a young man returns to cultivate his father’s farmland so long devastated and abandons due to the negligence of those who had alienated it. And free once more, like the bird that leaves his cage, like the flower that returns to the open air, they will discover their good old qualities which they are losing little by little and again become lovers of peace, gay, lively, smiling, hospitable, and fearless.”[13]

The Manunggul Jar is a symbol of the NationalMuseum’s important role in spearheading the preservation the cultural heritage—pamana—using multi-disciplinary techniques. It is a testament of how art can be a vessel of history and culture with the help of scholars. In this light, a simple jar becomes the embodiment of our experience and aspirations as a people and how we must look at ourselves—Maka-Diyos, Makakalikasan, Makatao at Makabansa. [14]

I have visited the Manunggul Jar numerous times since that April day in 1995 at the Kaban ng Lahi room of the National Museum II—The Museum of the Filipino People (former Department of Finance Building) where it has been moved since my first visit and everytime I look at it I am reminded of how great and compassionate my nation is and how I could never be ashamed of being a Filipino. Everytime I look at the Manunggul Jar, I see a vision that’s hopeful that a new generation of Filipinos will once more take the ancient balanghay as a people and be horizon seekers once again.[15]

Palm Sunday, 1 April 2007, 05:00 PM

#2046 FacultyCenter, Bulwagang Rizal,

UP Diliman, Quezon City

SOURCES CITED:

Abrera, Bernadette Lorenzo. “Ang Sandugo sa Katipunan,” in Ferdinand C. Llanes, ed, Katipunan: Isang Pambansang Kilusan. Quezon City: Trinitas Publishing, Inc., 1994, p. 93-104.

ADHIKA ng Pilipinas, Inc. Kasaysayang Bayan: Sampung Aralin sa Kasaysayang Pilipino. Manila: National Historical Institute, 2001.

Bautista, AngelP.Tabon Cave Complex. Manila: NationalMuseum, 2004.

Bellwood, Peter. “Hypothesis for Austronesian Origins,” Asian Perspectives, XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 107-117.

__________. “The Batanes Archaeological Project, and the CurrentState of the ‘Out of Taiwan’ Debate with Respect to Neolithic and Austronesian Language Dispersal.” Lecture delivered among the faculty of the UP Department of History, Palma Hall 109, UP Diliman, 28 March 2006.

Covar, Prospero R. Kaalamang Bayang Dalumat ng Pagkataong Pilipino (Lekturang Propesoryal bilang tagapaghawak ng Kaalamang Bayang Pag-aaral sa taong 1992, Departamento ng Antropolohiya, Dalubhasaan ng Agham Panlipunan at Pilosopiya, Unibersidad ng Pilipinas. Binigkas sa Bulwagang Rizal, UP Diliman, Lungsod Quezon, Ika-3 ng Marso, 1993).

EDSA 2000: Landas ng Pagbabago, a documentary of the People Power Commission, narrated by Vicky Morales and Teddy Benigno, directed by Maria Montelibano, broadcast date: February 2000 at NBN-4 and ABS-CBN 2.

Fox, Robert B. The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavations on Palawan Island, Philippines. Manila: NationalMuseum, 1970.

Maceda, Teresita Gimenez. “The Katipunan Discourse on Kaginhawahan: Vision and Configuration of a Just and Free Society,” in Kasarinlan: A Philippine Quarterly of Third World Studies, 14, Num. 2, 1998, pp. 77-94.

Quibuyen, Floro C. A Nation Aborted: Rizal, American Hegemony and Philippine Nationalism. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila U. P., 1999, p. 215-216.

“Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 8491, series of 1998, The Code of the National Flag, Anthem, Motto, Coat-of-Arms and Other Heraldic Items and Devices of the Philippines” in The Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines illustrated (Manila: National Historical Institute, 2006).

Salazar, Zeus A. “Ang Kamalayan at Kaluluwa: Isang Paglilinaw ng Ilang Konsepto sa Kinagisnang Sikolohiya” in Rogelia Pe-Pua, ed., Sikolohiyang Pilipino: Teorya, Metodo at Gamit. Quezon City: Surian ng Sikolohiyang Pilipino, 1982) pp. 83-92.

Scott, William Henry. Filipinos in China Before 1500. Maynila: China Studies Program, De La Salle University, 1989.

Solheim, Wilhelm II, G. “The Nusantao Hypothesis: The Origins and Spread of Austronesia Speakers,” Asian Perspectives XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 77-78.

Valdes, Cynthia Ongpin. Archaeology in the Philippines, the National Museum and an Emergent Filipino Nation. Online, internet. Available URL: http://homepages.uni-tuebingen.de/alfred.pawlik/Solheim/philippine_archaeology.html.

[1] First submitted as a reaction paper for Dr. Maria Mangahas’ Anthropology 219 (Special Problems in Museology) class for the second semester, 2006-2007 at the University of the Philippines at Diliman. The author expresses deep gratitude to his former student, Ms. Patricia Janine A. Icatlo, who edited this paper. Ms. Icatlo is a Film student at the University of the Philippines at Diliman, and also served as News Sectional Editor of the St. Claire School Junior Journal (St Claire School, West Ave., Quezon City), and Internal Associate Editor of Forum (Rogationist College, Silang, Cavite).

[2] Cynthia Ongpin Valdes, Archaeology in the Philippines, the National Museum and an Emergent Filipino Nation (online, internet. Available URL: http://homepages.uni-tuebingen.de/alfred.pawlik/Solheim/philippine_archaeology.html).

[3] Angel P. Bautista, Tabon Cave Complex (Manila: National Museum, 2004), p. 49.

[4] Robert B. Fox, The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavations on Palawan Island, Philippines (Manila: National Museum, 1970), pp. 112-114.

[5] Wilhelm G. Solheim, II, “The Nusantao Hypothesis: The Origins and Spread of Austronesia Speakers,” Asian Perspectives XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 77-78; and Peter Bellwood, “Hypothesis for Austronesian Origins,” Asian Perspectives, XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 107-117.

[6] ADHIKA ng Pilipinas, Inc., Kasaysayang Bayan: Sampung Aralin sa Kasaysayang Pilipino (Manila: National Historical Institute, 2001), pp. 25-32.

[7] Peter Bellwood, “The Batanes Archaeological Project, and the CurrentState of the ‘Out of Taiwan’ Debate with Respect to Neolithic and Austronesian Language Dispersal.” Lecture delivered among the faculty of the UP Department of History, Palma Hall 109, UP Diliman, 28 March 2006.

[8] William Henry Scott, Filipinos in China Before 1500 (Maynila: China Studies Program, De La Salle University, 1989), p.1.

[9] Zeus A. Salazar, “Ang Kamalayan at Kaluluwa: Isang Paglilinaw ng Ilang Konsepto sa Kinagisnang Sikolohiya” in Rogelia Pe-Pua, ed., Sikolohiyang Pilipino: Teorya, Metodo at Gamit (Quezon City: Surian ng Sikolohiyang Pilipino, 1982) pp. 83-92; and Prospero R. Covar, Kaalamang Bayang Dalumat ng Pagkataong Pilipino, p. 9-12 (Lekturang Propesoryal bilang tagapaghawak ng Kaalamang Bayang Pag-aaral sa taong 1992, Departamento ng Antropolohiya, Dalubhasaan ng Agham Panlipunan at Pilosopiya, Unibersidad ng Pilipinas. Binigkas sa Bulwagang Rizal, UP Diliman, Lungsod Quezon, Ika-3 ng Marso, 1993).

[10] ADHIKA ng Pilipinas, pp. 81-92.

[11] Bernadette Lorenzo-Abrera, “Ang Sandugo sa Katipunan,” in Ferdinand C. Llanes, ed, Katipunan: Isang Pambansang Kilusan (Quezon City: Trinitas Publishing, Inc., 1994), p. 93-104; and Teresita Gimenez-Maceda, “The Katipunan Discourse on Kaginhawahan: Vision and Configuration of a Just and Free Society,” in Kasarinlan: A Philippine Quarterly of Third World Studies, 14, Num. 2, 1998, pp. 77-94.

[12] EDSA 2000: Landas ng Pagbabago, a documentary of the People Power Commission, narrated by Vicky Morales and Teddy Benigno, directed by Maria Montelibano, broadcast date: February 2000 at NBN-4 and ABS-CBN 2.

[13] Translation cited in Floro C. Quibuyen, A Nation Aborted: Rizal, American Hegemony and Philippine Nationalism (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila U. P., 1999), p. 215-216.

[14] The motto of the Republic of the Philippines according to section 45, Artcle III of the Flag and Heraldic Code. “Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 8491, series of 1998, The Code of the National Flag, Anthem, Motto, Coat-of-Arms and Other Heraldic Items and Devices of the Philippines” sa The Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines illustrated (Manila: National Historical Institute, 2006), p. 48.

[15] My very last requirement in my course work for my MA History (before my penalty course) is dedicated with gratitude and affection to my mother Vilma and my father Charles—let no one stand up and say they didn’t raise me with love and honor, for their proud son praises the Lord for being brought forth in the world by them.