AN OLD BANDUNG-RELATED BOOK REVIEW

To celebrate Sejiwa: The Spirit of Bandung at 70: A Hybrid International Conference on the Asian-African Conference of 1955.

Laurel Report: Mission To China

By Senator Salvador H. Laurel

Manila, April 1972,

185 pages

Reviewed by Xiao Chua in 2003.

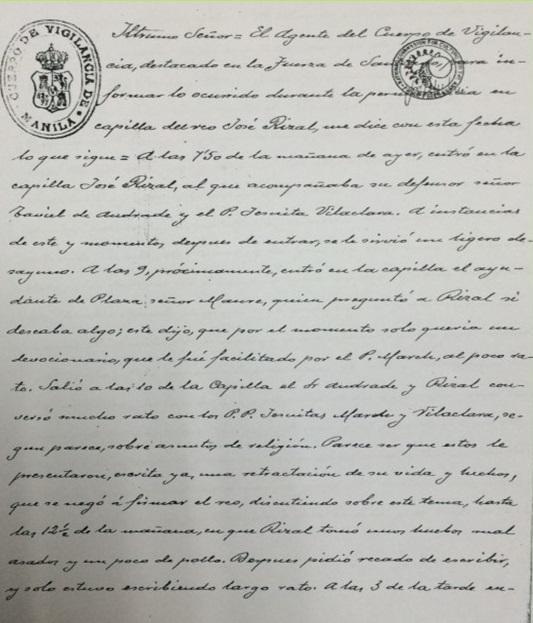

This is basically the report by then Senator Salvador “Doy” Laurel to Senate President Gil J Puyat on the merits of his official journey to China on 12-22 March 1972, a few months before President Ferdinand Marcos’s declaration of Martial Law and the abolishment of the Senate. This is a very interesting document because it was an insider’s glimpse of how China and the Philippines dealt with each prior to the establishment of formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic Of China—both politically and culturally. In 1949, when the PRC was established, under American influenced, we broke our diplomatic ties with China, with the impression that Communism is against the principles of democracy. The book is also interesting as it touched many issues on China then that greatly affected Asian diplomacy even to this day.

On the invitation of the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, Laurel embarked on a journey to China accompanied by, among others, his lovely wife, Mrs. Celia Diaz-Laurel, who became his secret weapon as she became the diarist, photographer and interpreter in Mandarin! His mission: gather data and materials that would be useful to the re-opening of trade relations with China as the one and only committee member to make an observation tour of that country. Within his ten-day visit, he met various Chinese ranking officials. They planned to meet Premier Chou En Lai, but the contingent decided to leave on 21 March. Nevertheless, Laurel’s discussions with lower ranking Chinese officials were very substantive.

To understand Chinese foreign policy, one should know their five principles promulgated at the Bandung Conference (or the Pancha Sila), it’s their Bible in diplomacy: “1. Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, 2. Mutual non-aggression, 3. Mutual non-interference in each other’s intern affairs, 4. Equality and mutual benefit equality and, 5. Peaceful co-existence.”[1] This could be seen with their statement, a direct attack on American imperialism,[2]

The People’s Republic of China will never be a superpower. We belong to the Third World. To be a superpower is to interfere with the affairs of other nations. To be a superpower is to dominate and control other nations. It means bullying weaker nations.[3]

China expressed their desire to resume diplomatic relations with the Philippines stating the fact that we’re really natural neighbors and that we’ve been friends for a thousand years and was only interrupted for 23 years. But before resuming relations, the Philippines should have a common view with them on the Taiwan issue. Laurel agreed with this saying that “the Two-China policy is unrealistic, deceptive and wishy-washy policy. Recognizing Taiwan as the government of China in effect means that Taipei is the seat of government of the 800 Million Chinese in the mainland.”[4]

The Philippines’ claim on the on the oil-rich Spratley Islands, also known as Freedomland, was also brought up in the discussions. According to the Chinese, they always regarded the islands as theirs, even called it Nansha Islands but said that it wasn’t yet the right time to talk about the issue because of the absence of diplomatic relations.[5]

Laurel asked if the anti-Maoist Anti-Subversion Law would be an obstacle in China-Philippine Relations. Take note that Mao Zedong was still alive at the time Marcos declared war to the communists in the Philippines for their adherence to the Marxist-Leninist-Mao Zedong thought.[6] The Chinese answered that it’s an “internal problem that is up to the Philippines to resolve.”[7]

About trading, the Chinese said that they could “trade only on an unofficial or non-governmental or people-to-people basis.”[8] (Italics supplied) They couldn’t deal with the government because of the absence of diplomatic relations, and to have diplomatic relations, it is crucial to do away with the Two-China policy.

Considering all that was said, Laurel recommended that the Philippines do away with the policy of fear and ignorance towards China and the policy of subservience towards America that hinders us to have diplomatic relations with China. That if we would like to trade with China as a nation we should agree that there is only One-China, and its Central government is in Beijing. Laurel said,

Philippine-China relations have hitherto been one of snobbery, if not outright hostility. Our two peoples have been separated by a curtain of ignorance and mistrust….[9] We should forget the prejudices of the past and look forward to the promise of the future…. Finally, we are making it known that, paraphrasing the words of the great Recto, “We shall make no enemy if we can make a friend.”[10]

And after a few years, the Philippines and China re-established their diplomatic relations, adapting the recommendations of Laurel.

The rest of the book contains their China Diary that dealt mainly with cultural exchange with their Chinese hosts, texts of declarations and conferences such as the US-China Joint Communique, export and import corporations of the PRC, a primer on China, and the text of the Chinese Constitution as amended in 1954.

The book was very indispensable if you want to know about the real and official stand of the Chinese government on issues three decades ago. That’s why interested China watchers should consult first this book, and compare it with Chinese policy now and you’ll see that the Chinese government had become consistent on many issues but changed a bit with how they would deal with the United States.

In my opinion, Laurel had been very effective as a diplomat with his choice of words. And the way he dealt with the Chinamen and the way he wrote the report were brilliant and very effective in convincing those concerned and in meeting his ends. We should learn from his example. For students of diplomacy, the Laurel Report: Mission To China is a must read.

-11 March 2003

[1] Laurel, Salvador H. Mission To China. ( Manila, April 1972), p. 75.

[2] Then—China is against the US and their brand of imperialism. Mao even called US a Paper Tiger. Now—China is taking a more friendly approach towards the US. A reporter once wrote that since Mao met with Nixon in Feb. 1972, “The two countries have learn since then that they are doomed to live with each other….” (Liu, Melinda. “In Love With A Vision.” Newsweek 20 September 1999, p. 40.)

[3] Laurel, p. 5.

[4] Ibid., p. 25.

[5] Yet, even with the establishment of diplomatic relations, the Spratley issue is everything but resolved. In 1994, China asserted its claim by building two concrete structures at Mischief Reef or Panganiban, an area being claimed by the Philippines. (Magno, Alex. “Naval Power Play Sets Off Alarms.” Time 27 Sept. 1999, p. 106.)

[6] But when Marcos visited Beijing, he told the Maoists,

I am confident that I shall leave inspired and encouraged in our own modest endeavor in the creation of a New Society for our people, for the transformation of China under the leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong is indeed the most noble monument to the invincibility of an idea supported by the force of human spirit. (Italics mine—quoted in Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., Testament From A Prison Cell (Makati: Benigno S. Aquino Jr. Foundation, Inc, 1984), p. 9.)

[7] Laurel, p. 12.

[8] Ibid., p. 9.

[9] Ibid., p. 25.

[10] Ibid., p. 42.