Perspective Check (for The Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook)

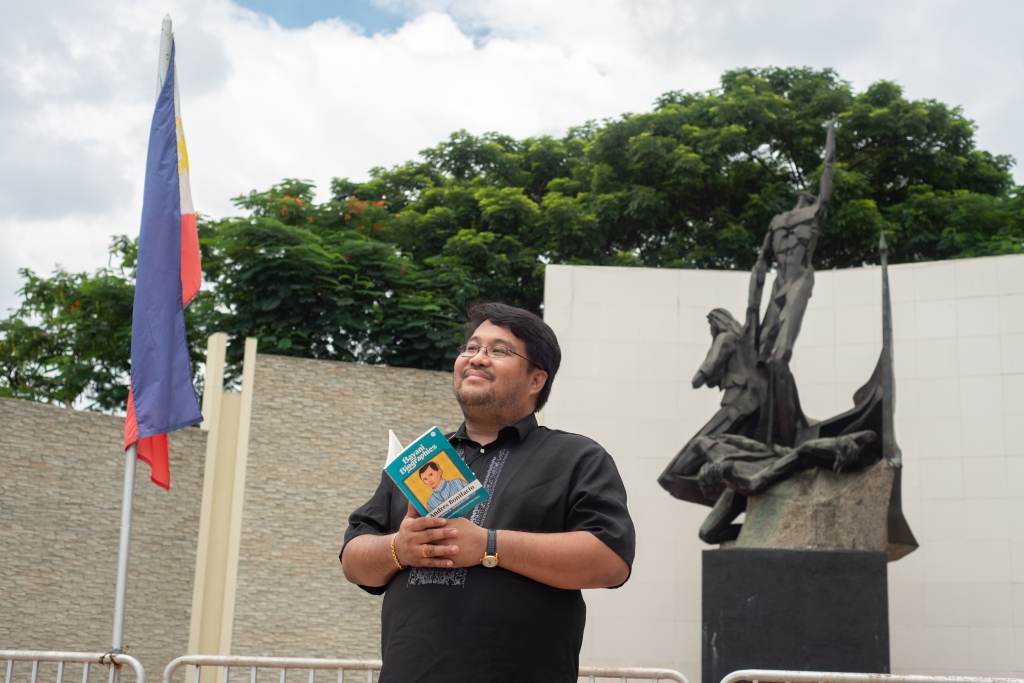

What is the way forward for historians and public history in today’s increasingly polarized climate? Michael Charleston “Xiao” Chua explores the question and revisits the role of history in our national life.

When talking about history as a public historian, some say I should be totally objective and be non-political. But can it be divorced from politics? Aristotle himself said, “man is a political animal” and that “every man, by nature, has an impulse toward a partnership with others,” Historian Teodoro Agoncillo echoed the sentiment, saying, “No true historian can disengage himself from the object of his study, for he is too much of a human being to repel his own nature.”

While some people who believe historical discourse should be confined to the academe to remain scholarly, even before academia was invented or introduced in this country, historical discourse had always been “public.”

If we take into account historian Zeus A. Salazar’s analysis of our native word for “history,” i.e. “kasaysayan”—the root word “saysay” translates to both story and relevance—we can say that the precursor of historical discourse came from the epics and myths chanted by the babaylanes, local religious leaders, healers and storytellers; and the binukots or the community maidens. Their stories united the community; the oral traditions, while not always factual, reflected their real beliefs, characteristics, and aspirations. When the “bayan” or the community listened to stories of the past, they would feel that they were one people, sharing the same past and future, journeying the same boat.

That is why the orality of “chismis,” where writing was only prevalent to our ancestral elites, can actually be part of historical analysis, not as a measure of factuality of events, but of mentalities of those who shared the oral stories.

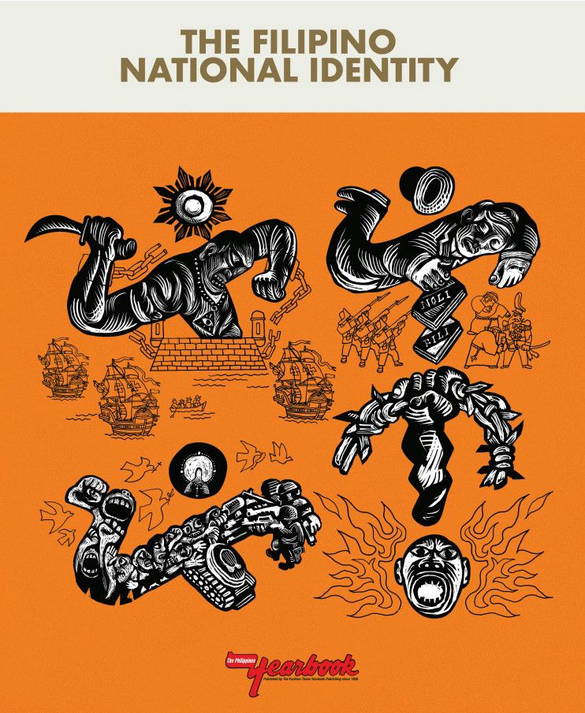

When the Spanish colonizers came, they showed us a bipartite view of history in their chronicles. There they described our lives before the conquista as dark, uncivilized, and without progress, with them introducing us to the “maravillosa civilizacion christiana” (Wonderful Christian Civilization). Despite our dynamic culture syncretising with Catholic culture, we came to depend on Spain as the giver of enlightenment, which helped subjugate us.

The Spanish writer José Felipe del Pan urged Filipinos to write history in their own perspective. Father José Burgos, Pedro Paterno, Isabelo de los Reyes and eventually José Rizal, T. H. Pardo de Tavera and many others will make studies on our ancestors and develop what Zeus Salazar would call the legacy of the Propaganda Movement—“the Tripartite View of History.” That is: before colonialism, our ancestors were progressive and had an elaborate civilization, and then colonialism came and there was darkness. They used history to campaign to Spaniards for the third part of history: A life of “kaginhawahan” because the colonizers reformed Las Filipinas.

Although La Propaganda politically failed, its writings gave a sense of oneness and nationhood to the Filipino reading elite. But Andres Bonifacio, the Father of the Filipino Nation, will appropriate the tripartite view of history and write in his people’s language in the 1890s to urge his compatriots to fight and die to give birth to the aspired nation in “Ang Dapat Mabatid ng mga Tagalog.” The national sentiment was fostered among many, such that thousands of Filipinos rose in 1896 to fight for independence during the Philippine Revolution and established their own national governments, the Haring Bayang Katagalugan headed by Bonifacio as President, an indigenous concept of nation that goes back to our Austronesian maritime historical roots (taga-ilog), and subsequently, the first constitutional democratic republic in this continent, the Republica Filipina headed by Emilio Aguinaldo, established in 1899.

When the Americans came, their sentimental imperialism wanted them to be the best imperialists, to win the hearts and minds of the Filipinos. They hired researchers, headed by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, who translated all available Spanish documents showing our history before and during colonialism and they came up with a 55-volume work The Philippine Islands 1493-1898 (also known as the Blair and Robertson). Boy, oh boy, the Americans knew our soft spots. Despite the bloody Philippine-American War, the way they framed the public school system as their heritage despite giving us a colonial education, made us look favorably towards them to this day.

After the revolution and on the onset of the 20th century, the careers of politicians and former revolutionary leaders were at stake as they invoke the names and images of national heroes, battling the spotlight in newspapers about their version of history. Manuel Quezon, Jose P. Laurel, among others, used it to rally people in their campaign for independence.

After the Second World War, veterans and many Filipinos used the commemorations of that war to remind the US of how we fought together as partners and ask for rightful reparations and compensation. On the other hand, nationalist politicians like Claro M. Recto, and subsequently nationalist historians Teodoro Agoncillo and Renato Constantino would use history to remind us of American neo-colonialism that continued even after independence. This kind of historiography will even be used by rebels and revolutionaries as Amado Guerrero (José Ma. Sison) in his book Philippine Society and Revolution, to remind people to take the cause of the oppressed.

Strongman Ferdinand E. Marcos knew the power of history and culture, using it to justify his 20-year rule, from proliferating the ancient myth of the “Malakas and Maganda” (reincarnated to Ferdinand and wife Imelda) and the Ilocano folk hero Lam-ang (in the epic reincarnated by a person named Marcos), to commissioning historians to write a multi-volume work titled Tadhana: The Story of the Filipino People under his by-line and authorship (notably still the best work on the 16th to 18th century Philippines). Marcos also rekindled the ancient barangay leadership and shaped himself to become the modern datu, or even, the modern Kalantiyaw (although eventually this ancient lawgiver was exposed to come from a hoax).

The memory of the people’s revolution of 1986, also known as EDSA People Power, was invoked by many of its participants to advance their political gain. Many human rights advocates also used it to advance consciousness on the importance of democratic rights. This time of soul searching also strengthened the movement to indigenize Philippine History in the academe such as the Pantayong Pananaw by its adherents headed by Zeus A. Salazar, as the nation moved forward to its 100th birthday in 1998. Such commemorations paved the way for an explosion of public history in the media, including the television show Bayani.

The election of Noynoy Aquino in s2010 rekindling the memory of People Power was expected to institutionalize this perspective of history, yet the guy had much delicadeza. Except in official commemorations, the PNoy team avoided making self-serving histories using the people’s money. Manolo Quezon’s team in the Presidential Communications Office, instead of edifying the people power narrative, went back to the basics and sorted out our political history by digitizing and putting out Philippine institutional papers and photographs for the people to have a basic official history in the Official Gazette. From 2012 to 2017, the government station PTV4 also launched the TV segment Xiao Time.

Beginning in 2011, a deliberate attempt to attack the People Power narrative and restore the luster of the Marcos name seemed underway in social media. By strategically aligning themselves to the popular Rodrigo Duterte, the pro-Marcos propaganda machine touched on the fears, frustrations and aspirations of the people and used sensational language to sow division in the nation and galvanized those frustrated with the democratic institutions. This paved the way to the election of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Romualdez Marcos, Jr. as president.

What is the way forward for historians and public history in such a climate? Agoncillo also wrote that, “though history is not objective, it must nevertheless be impartial. Impartiality implies the moral responsibility of a historian to weigh the pieces of evidence and to derive just conclusions therefrom.” One can have a political stand but can also be fair. Perspectives and judgments are a must in studying history but methodology and fairness lessen biases.

History has always been a battlefield; we cannot undo that. But to borrow Canadian historian Margaret MacMilan’s words, we should always be aware of the “uses and abuses of history.”

We will further polarize the nation if we will be too intolerant. We must allow many perspectives, yet we should uphold the importance of evidence. Because, as we can see with the ancient babaylan, the role of history and of the storyteller is to edify and unify the nation with stories that inspire them to be better Fiipinos. History can be used to enslave us with rage, but we aspire for a history that inspires, liberates and empowers the people.

In a time when some wants us to forget, it is courageous to remember and remind people that history should be the story of liberty.

25 July 2022

My thanks to guest editor Manuel Quezon III and Ditas Bermudes for the trust. Please read context: https://www.facebook.com/sirxiaochua/posts/pfbid0jZRMg2RdjKLH9BGtnP2hg5NoTAJVVELeHK1XzEiwrGjh9vZ4hEE6TESzdyUnwBhWl