‘I am the Philippines’: A reflection on Quezon and kabayanihan

The Manila Times, Walking History Column by Xiao Chua

July 1, 2025

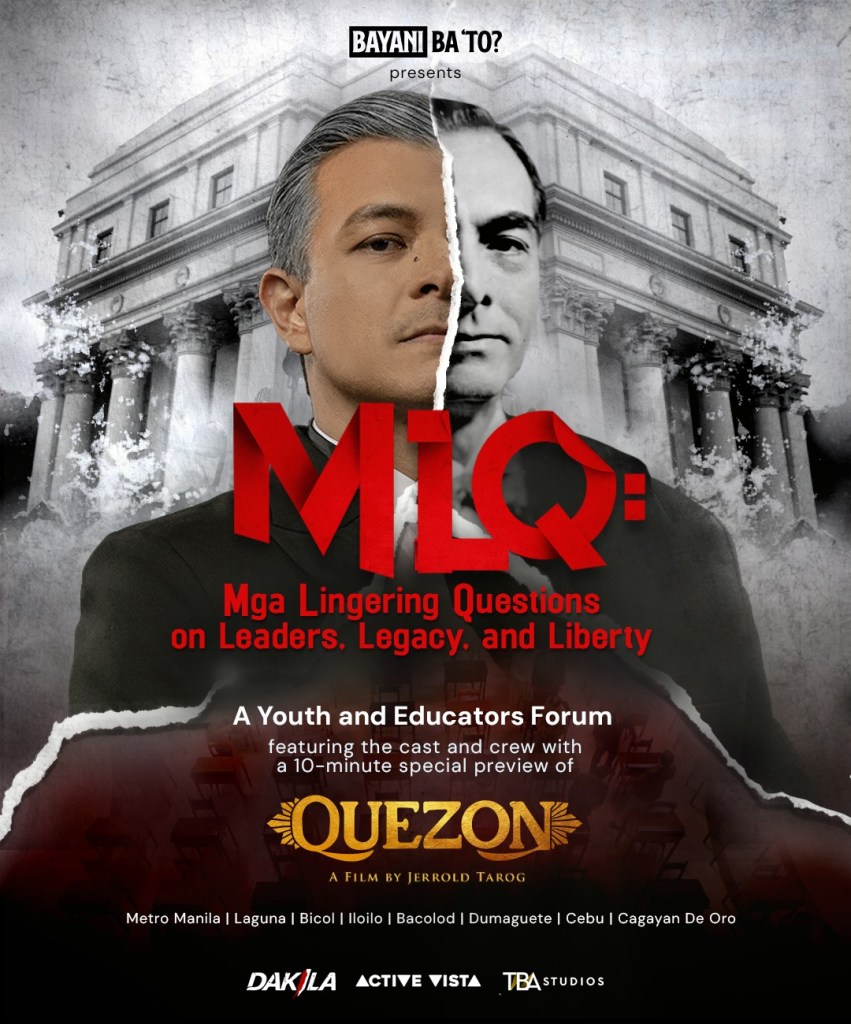

SOON, Jerrold Tarog’s “Quezon” will come out in the cinemas, the third installment in the ‘bayaniverse’ of TBA Studios. Since the first film, “Heneral Luna” in 2015 and “Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral” in 2018, Dakila, a collective promoting Filipino heroism, has been tapped to conduct a nationwide tour to promote the films under the project “Bayani Ba ‘To” (which alludes to heroes as monuments but also to a question about their heroism), where historians like John Ray Ramos, Alvin Campomanes, Natasha Kintanar and myself lead the discussions. The warts-and-all approach of the films makes them more appealing than the almost hagiographic approach to the teaching of heroism.

Last June 23, 2025, the historians, Dakila and a representative of TBA met to consolidate our insights on how to contextualize “Quezon” (without spoilers).

Answering the question, “Was President Manuel Quezon a bayani?” is more complicated than perhaps asking, “What was his contribution to Philippine history and to us Filipinos?” Arguably, Quezon is the “Architect of the Modern Philippine State.” And he was able to do it because, as a pioneer actual national leader of the country, he assumed a cultural role familiar to the people, a “datu,” whose role in indigenous society is to distribute “karangalan” (honor) and “kaginhawaan” (well-being) and was also the chief bagani (warrior). When the Spanish colonizers came, the datu class became the principalia class, who became the bridge between the people and the colonial masters. The survival of the system rests on negotiating with the colonizer in order to continue governing and providing for the people. This continued when certain elites were given favor by the American imperialists.

Add to this mix, according to fellow Manila Times columnist Van Ybiernas, the fact that a whole generation of potential heroic leaders was wiped out during the Philippine Revolution, like José Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Emilio Jacinto, etc. Those who remained in the same patriotic spirit when the Americans came, like Macario Sakay, were wiped out too. That nationalist route would lead to death. And so, Quezon’s generation figured that they should creatively show nationalism in front of the people while patronizing the Americans for survival.

This is the reason why Quezon was described as “janus-faced”: He said one thing to the people, and another to the elite and the imperialists. And since the Americans were the only colonial power to promise independence to their subjects as the Jones Law was passed, nationalism and loyalty to America had no contradiction. This is how Quezon helped create a nation in the face of American imperialism: He had to have transactional relations with the elite and the Americans so he could provide for his people. In his imaging (“papogi”), he created a cult of personality, the heroic datu who facilitates “kaginhawaan,” which is the basis of the patronage politics in our present society.

So yes, there were the two sides of Quezon. The one who told his daughter Zeneida, or Nini, “Never forget the poor.” He was the visionary who put forward “social justice” as the banner cry of his leadership, that there should be a preferential option for the poor. He was radical in his empathy and inclusivity in allowing the women’s vote and the adoption of a national language. He demonstrated the Filipinos’ “kapwa” culture by implementing the eight-hour day and minimum wage, housing projects, and championed human rights by not implementing the death penalty, believing that no Filipino should beg for his life in his administration, and by rescuing 1,300 Jews from the Holocaust.

But he also institutionalized a traditional, patriarchal, transactional populist system which continued colonial dependency and elite democracy. This is Quezon’s contradictory legacy for good (and for bad). I guess we should give credit to where credit is due but also learn from his faults.

His batchmate, Emilio Jacinto, wrote, “Let us seek the light and do not let us be deceived by the false glitter of the wicked.” So, I will leave it to you to answer if Quezon was indeed a bayani. But I would like to end with a quote which Quezon was heard to have said toward the end of his life in reference, I believe, to Sergio Osmeña, his vice president: “Look at that man, why did God give him such a body when I am here struggling for my life? I am Manuel L. Quezon — I am the Filipino people, I am the Philippines.”

Truly, he once represented the Philippines, but now we always mistake loyalty to the leader as loyalty to the country and criticizing the leader as being disloyal to the nation. We have always depended on leaders and strongmen as our heroes. We always ask the question “Bayani ba ‘to?” But the hero we are looking for might be the image in front of us when we look at the mirror: “I am the Philippines, tayo ang Pilipinas, tayo ang bayan, tayo dapat ang bayani.”

“Pero bayani ba talaga tayo?” Let this be both a call for action and an aspiration. We are the Philippines. We have the power to change our country.